Asking better questions and learning to facilitate simple customer interviews is one of the fastest ways to bring customer-centred design into the boardroom. Customer learning is a powerful for developing strategy, and it’s not just their wants and needs. Learning their motivation, attitudes and behaviour helps to define products and services that have a chance of succeeding. Yet, many leaders choose to forego early opportunities to learn from customers because…

“There’s no time for that”

“We already know our customers”

“The marketing and customer insights team always do all of the research”

“We don’t have the right skills to do it properly”

While sometimes those are reasonable concerns, too often, it means customer insight is delayed so much that it becomes impotent. The purpose of research is to learn something to inform a decision about what to do next. It gives us confidence to continue, or a reason to explore new lines of enquiry. It’s how we find a path, and shape our beliefs about how we’re going to win. Most importantly, it’s helps decide where to invest. Leaders need research that helps them learn fast, make decisions, and keep moving.

Expert researchers have lots of ways to do the best research. We can be confident in their analysis, and those neat summary reports are a terrific reference. The trouble is that thoroughness takes precious time – a scarce resource for most teams. Insight that arrive weeks or months after the question is often irrelevant. Not because it’s wrong, but because the product team has already moved on to new questions to find answers to. Those questions need new research! And so it goes ad infinitum.

You can break the cycle by doing your own research in hours not weeks. Basic design research technique is a powerful tool that is easily learned. With some simple instruction and a little guidance, product teams can 10x their customer insight capability by connecting decision makers directly with customers.

Here’s how to get started.

Find better questions

Before asking questions, we need an idea of what answers we’re looking for. We need to design questions that push the conversation in a useful direction. Otherwise, we may have a lovely chat, but mightn’t learn anything that helps determine if we’re on the right track.

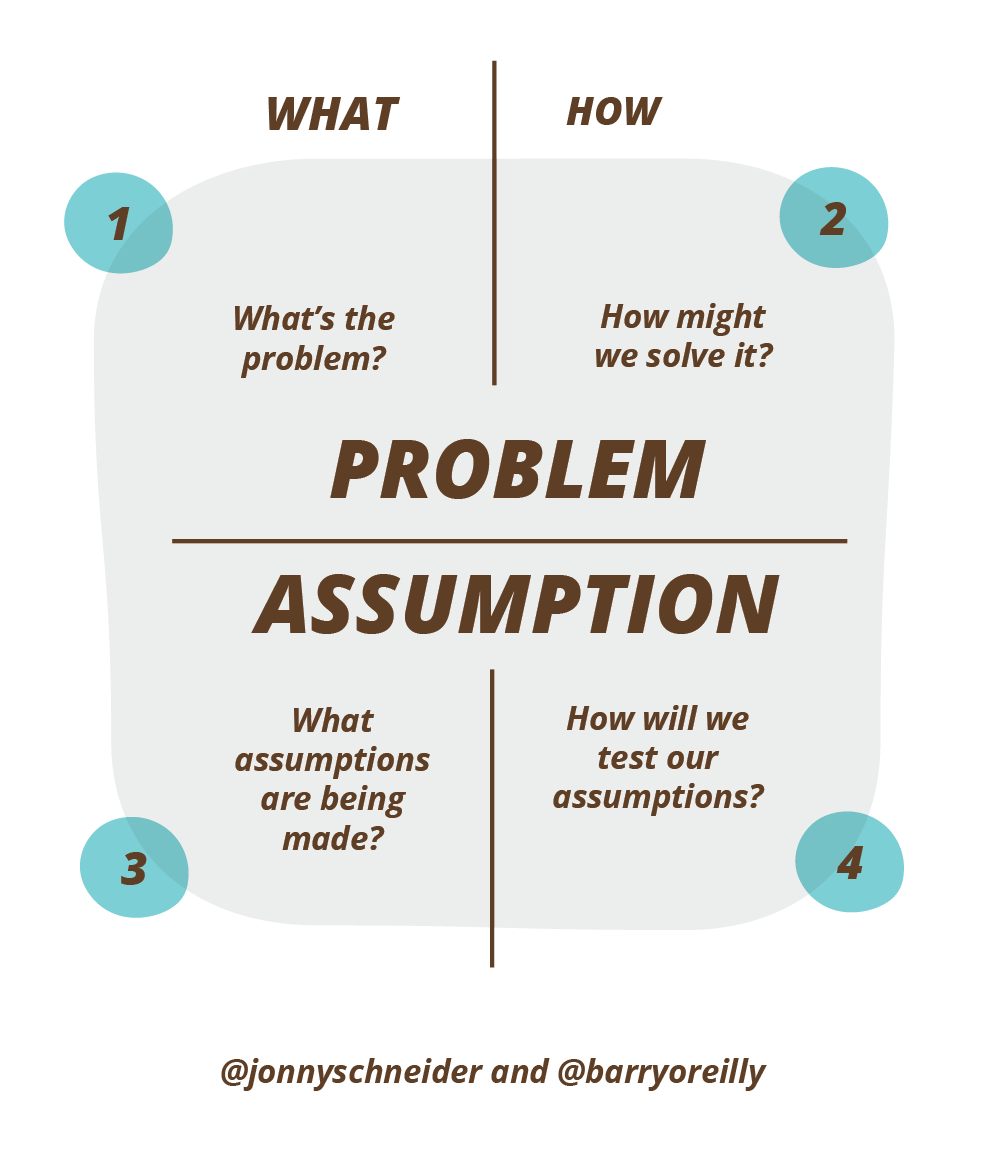

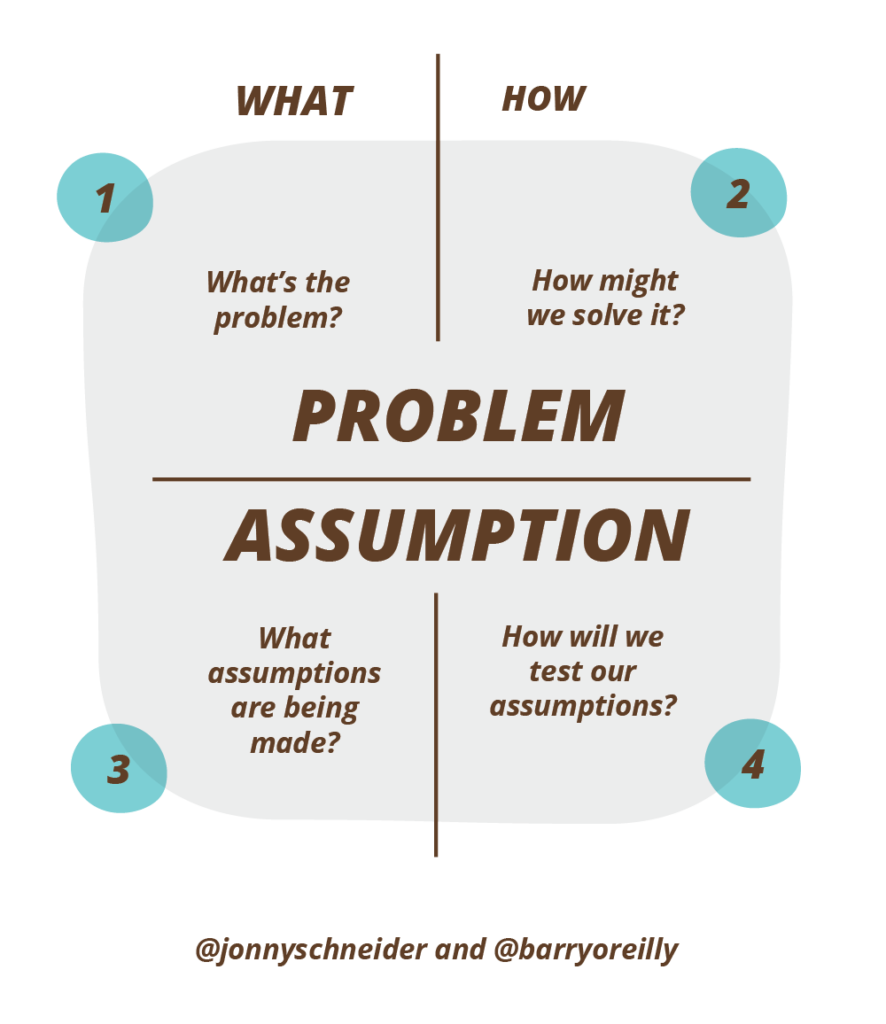

Everyone loves a quadrant model. They work because they’re simple. This one helps break down our beliefs and identify the underlying assumptions in our thinking. Those assumptions are then translated into questions that become the foundation of enquiry during customer interviews.

You’re a digital director at a personal investment company. Your competitors all have robo-advisory services, and the executive leadership team feels they ought to have one too. There are three months and $2M to make it so.

The solution is a robo-advisory service. We think it solves the customer job of managing a personal investment portfolio. What assumptions have we made? Traditional advisory services are out of reach. People will trust automated advice enough to make financial decisions. They’re willing to pay something for the service. Now we can design questions to find out if that’s true, and understand why or why not.

This simple approach is powerful because it’s flexible. You can start from anywhere – problems, solutions, assumptions or questions – and elaborate your thinking. It’s common start with a solution, and elaborate on the problem it solves. It’s easy to then identify implied assumptions, and these lead us to the questions that will help us learn from customers. As adoption for Design Thinking continues, more and more start with the problem, and then elaborate solutions, assumptions and questions.

With questions to answer, it’s time to talk to customers.

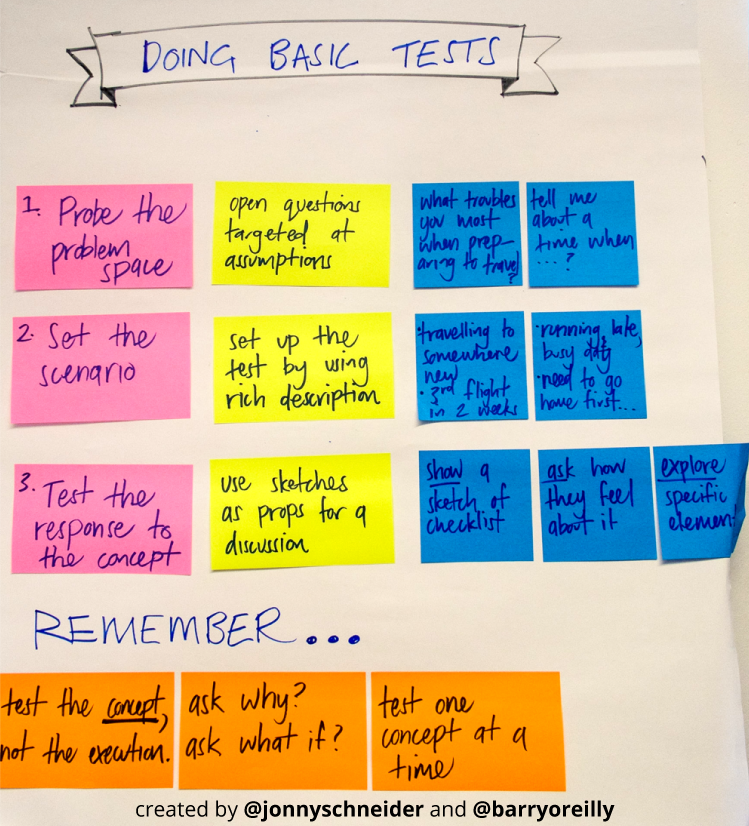

Do simple interviews

Talking with people is a great way to find out whether your ideas are worthwhile or hypotheses hold water. A professional researcher might do better interviews, but most people are capable of research that is good enough. You don’t need a certification to be an empathetic listener. Remember, it only needs to be good enough to inform a decision about what to do next. A lot of the time, the next thing is to explore a new question. It’s a quest for learning, not a quest for certainty, so the consequences of being ‘wrong’ are relatively low.

“Interviewing is a quest for learning, not a quest for certainty, so the consequences of being ‘wrong’ are relatively low.”

Just have a go, you’ll be surprised at how quickly you become competent. Follow these tips to get started.

1. Ask open, probing questions

Keep your questions open, not closed. You’re goal is to keep the participant talking. Meaning and insight is most often found in the stories that surround someone’s experience, not just the final outcome.

You’re working with Transport for London to improve the commuter experience. Knowing that Alessandra doesn’t like catching the train is a piece data. You can collect it by asking “do you like catching the train?”. That information is meaningless.

There’s more to learn by asking open questions, like “tell me about your experiences in travelling on trains”. You’ll likely get a more meaningful response. Alessandra might tell you about a seedy passenger with wandering eyes. It was an uncomfortable journey, and when this creeper alighted at Alessandra’s home station, she hesitated, feeling vulnerable, and decided to stay on the train for safety. This information is now much more meaningful, and might contribute to solutions that help travellers stay safe while commuting.

If you’re stuck for a question, or need a few seconds to gather your thoughts, try one of these:

| Like this… | Not like this… | |

|---|---|---|

| Ask open questions |

|

|

| Ask probing questions (instead of affirmative questions) |

|

|

2. Use description to set the scene

Using believable scenarios helps to prime people to think more deeply about how they might respond in a given situation. Its detail that might be skipped over otherwise. Even though we can’t rely on how people say they will behave, describing a scenario gives a chance that we’ll connect, and learn what people really think.

Don’t reveal an idea and ask for opinion. That’s conjecture. It’s much better to set a relatable scenario; describe a solution; observe the reaction; and ask further probing questions to better understand it. This works well in many situations, but is especially useful when combined with sketches, prototypes or other visual props that people can interact with.

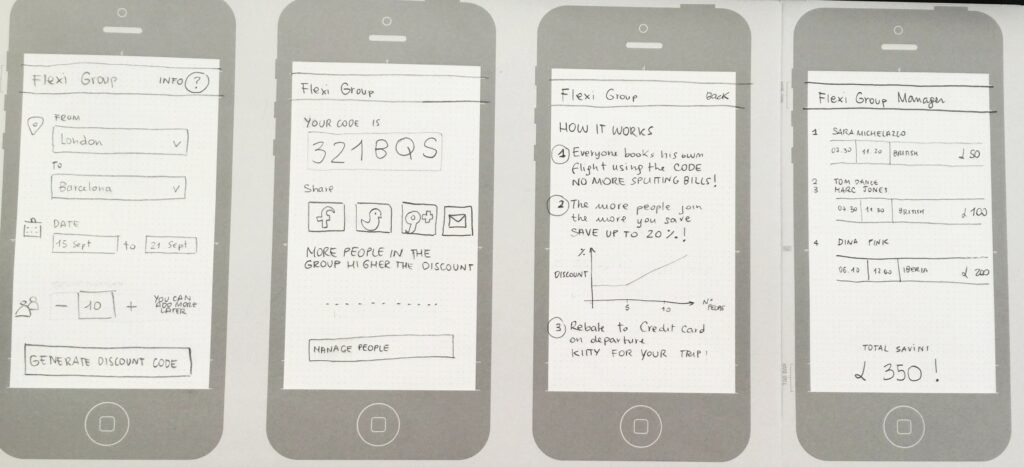

3. Use props to observe reactions

Using simplistic sketches is a fast and effective way to start testing assumptions. You’ve set the scenario, now show a solution as a sketch or rough wireframe and observe what happens next. So much can be learned by watching, not just listening.

“So much can be learned by watching, not just listening. ”

You’re testing a new proposition in a booking service that uses economies of scale to acquire new paying customers by offering group discounts. Success relies in-part on a belief that customers will tolerate a few extra steps and some social sharing to qualify for a small discount.

A picture is worth a thousand words.

What do you understand this to be? Tell me what sense you make of it? What would you do now? What might you do if…? What’s your expectation about what happens next? And so on.

The concept is now tangible and relatable. These visual props give people something more specific to share their thoughts about.

In summary

Talking with customers isn’t just for research experts. Embrace the entrepreneurial spirit, get out of the building, and find out straight from the people whether you’re thinking really adds up. Keep it simple and get involved. You’ll find that what you learn in one day talking with customers is more than you thought possible. Don’t do it once, do it always. And use what you learn to make better decisions faster. You’ve nothing to lose, and so much to gain.

They’ll be opportunities to do more thorough research later. As strategy evolves from initial learning, stakes are raised, investment increases, and experiments become more elaborate. That’s when to bring in the experts. They’ll have ways to increase confidence in any findings – often by using several methods to triangulate the results. Early on though, a general proximity to the truth is more important than precision.